I arrived in Stevens Hall, room 365 for my 8am Biomedical Ethics class to learn that I was now in charge of some of the public health policy at the University of Maine. This was surprising because my formal training is in philosophy.

In an email from March 25th, 2022, UMaine President Joan Ferrini-Mundy writes,

As a result of the current status of COVID-19 on our campuses and in Maine, we will go into the last six weeks of the semester with new face covering guidance. Effective tomorrow, March 26, face coverings will be optional for students, faculty, staff and visitors in non-classroom facilities on campus and in our facilities statewide, both indoors and out, regardless of vaccination status.

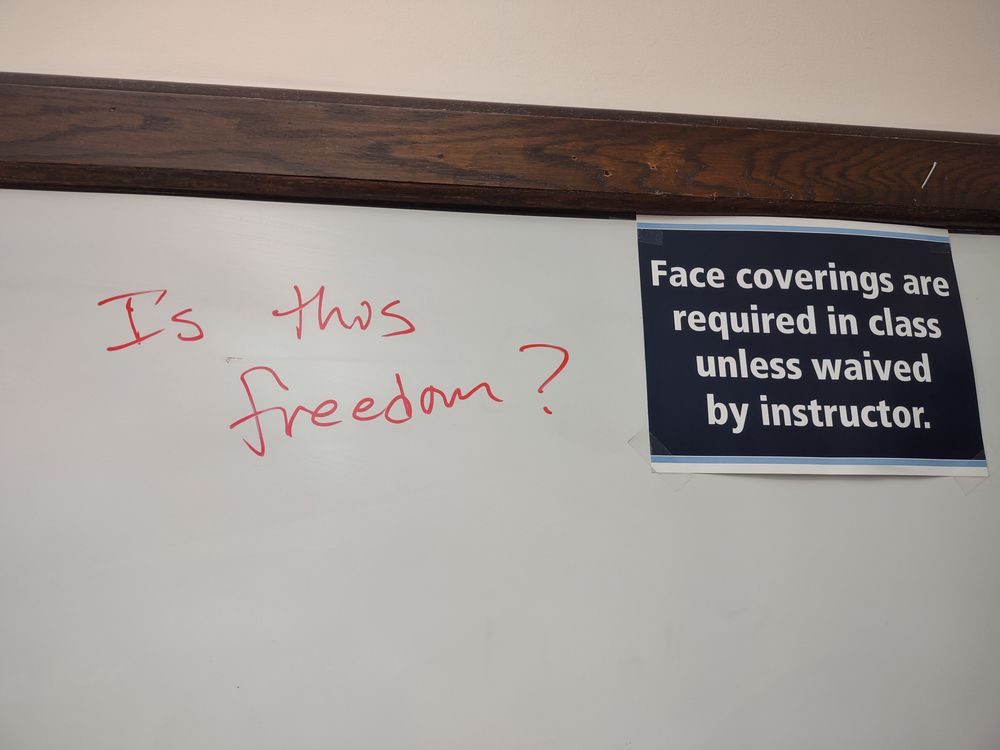

We will continue to wear face coverings in all classrooms, research spaces and instructional areas unless the requirement is waived by a faculty member. Signs in our classrooms will remind all of us that face coverings are required in class unless waived by the instructor.

Like many, I had become accustomed to skimming through emails from administration and so didn’t notice the qualification that masking in classrooms would be determined by the faculty. This means that Casey, a student in my 8am Biomedical Ethics class, had to draw my attention to the sign in the room stating this, giving me a very disappointed “Joe…” when she realized I wasn’t yet aware of the policy shift.

We were scheduled to read an essay about the imperative to “follow the science” during the pandemic. The piece dealt with the particular ways that underfunded public health organizations are organized and how this affects policy. Their recommendation was to start with local reform. Of course, by “local reform”, they did not mean putting philosophy professors, or those with expertise in accounting, sociology, or economics in charge of health care policy.

My first reaction was to note that, despite the way that we tend to conceive of freedom, I had no sense that this was increasing my freedom as an instructor. We tend to oppose “freedom” to “restrictions,” such that we take being free to mean removing any restrictions and any kind of restriction or limit is seen as an infringement upon, or diminishment of, one’s freedom. In this case, removing the restriction on masking, at least for me as the instructor if I so determine it, would result in greater freedom (for me). I have more choices, and so don’t I have more freedom?

This is not how I experienced it and I think we can see in this case how freedom is not simply increased with more choices and fewer restrictions. One reason is because I knew what I wanted to do from 8:00 to 9:15 in 365 Stevens Hall. I wanted to think through what it means to “follow the science” with my Biomedical Ethics students. I had a number of questions that we were set to deal with related to this issue like “What does it mean to follow the science’?”, “Do we have a duty to advocate for accurate information regarding COVID-19 with friends, family, or others?” and, if so, “What are the obstacles to completing this duty and how can we really make it happen?” I am not, in that case, made freer by having to think about whether or not I should require students to wear masks, different ways of managing the classroom, etc. I am, instead, burdened with a new responsibility. In addition to trying to engage the students on philosophical matters, there are a number of classroom management issues to consider, in addition to considering the best policy decision for this particular class at this particular time. This did not end up being a particularly significant burden in my case and did not ruin my ability to teach the class. Nevertheless, restrictions would, in this case, result in greater freedom.

Since it was a Biomedical Ethics class, we focused our attention on this issue. We proceeded to talk about how I might go about this. I asked students to tell me how it’s been going in other classes in order to start thinking about how we might best go about this. The options given were as follows:

- Majority Vote

- Authority (instructor decides)

- Minimum vote, whereby if one person wants us to be masked, we all wear masks

- Each student makes their own decision

We also thought that we could:

- Deliberate as a class

- Consult an expert (notice that this was the first time expertise was explicitly considered)

We talked about a few different ways that I might decide by authority. One of my students, for example, when describing what they’ve been doing, said “We’ve just been doing whatever makes the professor the most comfortable.” This is interesting, and not unlikely, but it is problematic. I don’t think there is a reliable moral principle that gives my health and comfort level a special priority in the classroom. Nevertheless, I could use the authority granted by the administration to implement whatever policy I wanted based on my own arbitrary inclinations.

A second use of authority, which for the time being I called “lazy authority”, was what I in fact was doing, which was to keep wearing masks because it seemed safest to continue with the status quo and delay making any new decisions.

A third use of my authority would be to “do my own research.” I could devote extra time to really try to figure out, to the best of my ability, the potential risks and benefits of wearing masks in this room with this specific group of people.

None of these seemed like sound moral decisions to implement on a university-wide scale. We tend not to think decisions should be made, on behalf of others or even for oneself, based on arbitrary inclinations. Thinking is promoted. We want to have good reasons for our views. Vesting me with the authority to research the issue on my own, or to consult the experts myself as much as I am able, may be the best we can do, but it is undesirable. I have no expertise in public health. In fact, given the kinds of students that take a class called “Biomedical Ethics”, many, or perhaps most of the students in fact have more expertise than I do on this issue. For that reason, giving me the authority in this particular situation seemed arbitrary.

Another option was to do a majority vote. Here we enter into political philosophy and democratic theory. Ideally, we would want to justify why this approach is best. It does seem to treat each person as equal. 1 person, 1 vote. However, we are immediately met with a concern about the “tyranny of the majority.” If 51% of the class agrees on one course, and, for example, tends to agree on many issues, they will always win. The rest of the members of the class will always lose every vote and will be a “persistent minority” within the system. This is a problem inherent in majority vote.

We could also just leave the issue up to each individual. This is a familiar type of thinking during the pandemic that fails to recognize the nature of what is at hand. We tend to think of ourselves and our choices on the individual level. I will take care of myself and make my decisions. You take care of yourself and make your decisions. However, issues like COVID-19 show us that thinking is too simplistic. When we sit together in a room in the context of an infectious disease, our health is interrelated. What you do affects me and what I do affects you. Put otherwise, masks work much better if everyone is wearing them. This is an issue where “following the science” is not easy, because we are constantly learning new information about this. It seems that masking alone can offer some protection, but it is particularly effective if everyone wears a mask.

The analogy we considered was smoking. Here, we know that leaving the decision up to each individual doesn’t really make sense, since if some are smoking, all are smoking in some sense. We recognized that in this case it isn’t a decision that each individual really makes solely as an individual when sitting in an enclosed space. In cases like these, we can extricate our individual decision for a decision made on behalf of a group.

This led us to consider a kind of “minimum vote”, whereby we would all wear masks if any one person wanted to wear them.There is a problem with thinking of each individual in a 1 person = 1 vote sense because the effects are not that straightforward. The harm that comes from wearing a mask during class is not equivalent to the harm that could come to someone if they were to contract COVID-19. This would be a way to recognize the differential impacts and levels of comfort that different individuals might have. It would also be a way to recognize the arbitrariness of having the instructor being in charge of public health measures in the classroom as opposed to any individual within that room.

In philosophy, we sometimes talk about an informal fallacy called the “appeal to false authority”. We see these often with celebrity endorsements of political candidates or spurious experts promoting supplements online. With COVID-19, “following the science” means following the appropriate authorities. It isn’t difficult to distinguish between Dr. Arel, their philosophy professor, and Dr. Walensky, an infectious disease expert and Director of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. But what about when the appropriate experts are in disagreement?

One thing that we’ve had to deal with during the pandemic is recognizing that science isn’t a monolithic enterprise that forms conclusions simply and definitively. We need to recognize that science is an ongoing process of reconsideration. Why would anyone think it’s anything else?

An internet news search for the terms “science says” gives the following headlines:

- Should shoes be worn indoors? Science says shoes are full of toxins and should be ditched at the door

- Science Says This is the ‘Most Boring Person in the World’

- Science Says Use the 1 Cup of Coffee Rule to Solve Difficult Problems

- Science Says The Average Crypto Investor Could Well Have Psychopathic Tendencies

- Science Says Your Notifications are Literally Driving You Nuts

- Even fish can solve math: Science says so

- The science says we need to remain vigilant about COVID

Despite what we may know about science, popular reporting on scientific findings talks about it as though it were a single thing with straightforward decrees. Given how we often talk about science, it is understandable that people end up thinking this way. Further, if this is how someone thinks about science, dealing with the changes in what we’ve been told throughout the pandemic would be a challenge. If science is supposed to be one thing, and we hear different things coming from different sources, our response may be skepticism. We may conclude that since there isn’t complete certainty, then there isn’t any certainty. “It’s an all or nothing thing” said one of my students.

We need to recognize that most of our daily reasoning is inductive. Inductive reasoning cannot yield absolutely certain conclusions, but that does not mean it is useless. It’s not really an “all or nothing” kind of thing. If we decide to quit smoking since studies suggest that it will likely cause health problems, we are using inductive reasoning. If I leave my office at 7:50 for my 8:00 class and have always arrived a few minutes early, I feel confident in continuing to leave at 7:50. This is still inductive reasoning.

Hume famously argued that all of our reasoning about cause and effect was based on induction. We are really “inferring” a causal connection between two events, like the cue ball hitting the 8-ball in pool. We see the cue ball move and then stop, and then the 8-ball starts moving. Hume argued that we are drawing the conclusion that the cue ball caused the 8-ball to move, not because we have uncovered any kind of physical law of nature, but because we have observed a recurring pattern. We assume that the future will be like the past, and conclude that the cue ball will move the 8-ball. Now, Hume isn’t saying that we shouldn’t think that it will, but is pointing out that even this very simple and seemingly straightforward kind of observation is induction.

My final class for the day was on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. We were also talking about the pandemic. Despite the fact that many of us are tired of talking about it, it’s a very potent issue that is on our minds. Our discussion of Aristotle was focused on what kinds of virtues are particularly important during the pandemic. Are we particularly called upon to display the courage to handle the fear that might surround us? Is this a time when it’s particularly important to maintain friendships despite the challenges? One that does seem particularly important is an intellectual virtue related to making decisions based on our understanding of the science at the time, and to recognize the nature of the kind of decision that we’re making. The reality is that we must make assessments about the danger to ourselves and others, and this may be relative to the situation, who is there, the relative number of cases in one’s community, the likelihood that someone that one might infect is vaccinated, etc.

Even if it would be better for such decisions to be made as a group, with expertise and sound judgment leading the way, we don’t have the option of waiting for that perfect world. We live in this one, and in this one we have to do things like make these decisions on our own, without much warning, and in ways that could affect many people.

We are no doubt developing habits of judgment, but Aristotle points out that both the bad and good lyre players become bad and good by playing the lyre. This is to say that simply doing it doesn't make you good. This is why we go to guitar teachers, for example. We are all making decisions about which situations are harmful, and we’ve developed a kind of sensibility related to when situations call for caution and when they don’t. We are developing habits. The issue that we should be concerned with is if we are making good habits or not. We have no choice but to make these decisions often. Ideally, we make them well.